Tea Party Pooper

I haven’t been paying much attention to what’s been going on in America this past week: theoretically, I’m on vacation. It’s been pleasant to have time to read, listen to music and to go out and experience Spring in England, even if that means getting rained on a few times.

I haven’t been paying much attention to what’s been going on in America this past week: theoretically, I’m on vacation. It’s been pleasant to have time to read, listen to music and to go out and experience Spring in England, even if that means getting rained on a few times.

However, I got a phone call from America yesterday; among other things, I was asked if I had seen anything in the British press about the Tea Parties.

“No,” I admitted, “but then again I haven’t looked for it.”

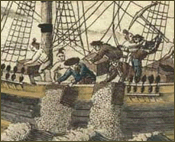

If my acquaintance’s estimate is to be believed, about 300,000 people gathered across the country on tax day, April 15, to protest at the high levels of government spending and taxation implied and stated by President Obama’s budget. This demonstration was supplemented by activists mailing tea bags to politicians; I can imagine the mild British retort about the quality of American tea making it unworthy for any other purpose.

Some commentators have tried to dismiss this as an irrelevance; while 300,000 across a country as vast as the United States does sound relatively minor by dilution, I don’t believe it is. I don’t believe it’s also right to say that this protest has no genuine echoes of the past. There was an alarming refrain from 1860; Governor Rick Perry of Texas said that his state had the right to secede if it wanted. The name “Appomattox” is apparently not one he’s heard before.

More fundamentally, the Tea Party of 2009, and its namesake in 1773 are similar in the following respect: a lot its energy came from an unwillingness for people to pay for public services which otherwise they will happily consume.

Perhaps one of the greatest (but most subtle) shocks I’ve experienced since moving to the United Kingdom was the shift in my perspective on the American Revolution. First, the British don’t call it the “American Revolution”; they refer to it as the “American War for Independence”. As many of the fundamentals of American governance were unchanged by the war (i.e., property rights, the rule of law), this is probably a more accurate moniker.

Second, I had the opportunity to look at the other side of the issue. The British perspective was actually very simple and utilitarian: they were not imposing taxes as part of some plan to impose tyranny on America. Rather, Britain had to raise cash to pay for the Seven Years War, which was fought between 1756 and 1763. When Americans talk about this particular war, they refer to it as the “French and Indian War”; this is accurate insofar as the American theatre was concerned (and furthermore it began in 1754), however the overall struggle was international and hugely expensive.

The French empire in 1756 rivalled that of the British; furthermore, their dominance of Louisiana, Quebec and all along the Mississippi River meant that the American colonists were essentially boxed in. Furthermore, the French were allied to the Native Americans (an exception were the Iroquois) who had an uneasy relationship, at best, with the Americans. If the colonies were going to be able to expand and thrive, this state of affairs could not be allowed to stand. War, in this instance, was welcome: there was no noticeable “peace movement” in the Thirteen Colonies during the conflict. Indeed, one of the more famous early portraits of George Washington show him dressed in a Virginia Militia uniform in preparation to battle the French.

The British won the war; the French were eliminated as a threat to the Colonies and the Native Americans’ resistance was crushed. Given the amount of men, materiel and money that had been expended by the Crown, it was not unreasonable for Britain to want a contribution from the Americans to help pay the bill.

If one subscribes to the hagiography of the Founding Fathers, this simple truth gets lost: if viewed through the fog of distorted history, the causes of the conflict change from a refusal to pay for services rendered, to the mighty issues of “taxation without representation” and preferring liberty or death to British rule. This is not to excuse the means by which the British imposed the tax: the proper method would have been to negotiate an arrangement with the colonial assemblies. There was also a disconnect between the London government and the colonists’ representation in Parliament. Finally, the British use of troops was incompetent and heavy handed, which led to the tragedy of the Boston Massacre. However, contrary to legend, George III was not a monster; he was certainly not an autocrat in the mould of King Louis XVI, with whom the Americans later allied, nor was the British government particularly possessed of evil intent. Again, it was simply short of money and needed the Americans to help pay the bills.

Having said all this, I could be branded a horrible traitor by many of my fellow countrymen. The hagiography of the Founding Fathers is extremely resistant to any alteration. I recall visiting Philadelphia in the mid 1990’s to attend my uncle’s wedding. Out of curiosity, I went to Independence Hall; I had not seen it since I was a small boy. I listened to the extremely earnest guide from the National Park Service talk about Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington in reverential terms. I invariably wanted to pipe up and present the British perspective on the matter; however, given the intensity with which the guide spoke, it would have been rude and tragic to interrupt his flow. It is still considered not apropos to ask what the Founding Fathers were really fighting for; certainly, they were men of genius, talent and character. However they were human beings, and as such, they were not infallible.

In many respects, those today who want to party like its 1773 are not out of line with tradition: the American government is short of cash. The services rendered are different: the wars are abroad rather than against a local enemy. Americans also appear to want the government to improve their health care beyond the obligations that Medicare already provides, they also want Social Security payments to continue to be made, they want unemployment insurance, and they want the government to provide a variety of subsidies and payments ranging from agricultural price supports to infrastructure projects. They have voted for solid Democrat majorities in the House and Senate, as well as for a Democrat President to ensure these services continue. There is a price tag associated with these demands; I no more accept the demonstrators’ protestations that they want small government than I would a (fictional) American colonist in 1756 saying that he didn’t mind the French building up their presence in North America. It may sound fine in theory: but when Social Security stops being paid or the Native American allies of the French burn down your homestead, the real-time consequences are sufficient, at least, to cause one to pause.

However, it is likely that the impetus behind the modern Tea Party movement will peter out. Today’s Tea Parties lack a John Adams or Thomas Jefferson to give a coherent theoretical and political edifice to the opposition, nor is there a Sam Adams to provide the necessary agitation: the likes of Rush Limbaugh and Ann Coulter are no substitute. Furthermore, President Obama’s recent call for ensuring America’s money is well spent indicates he has some understanding of how to defuse the issue: articulating clearly what the money is going towards forces the public to view spending as a specificity, a payment for services rendered, rather than a generality. Knowledge, rather than propaganda, can take the steam out of public anger. I would also suggest that he takes steps to get rid of earmarks, the majority of which can only be described as waste (a “Lawrence Welk Birthplace Museum” built in North Dakota springs to mind).

Finally, if President Obama wants to talk about history, there are plenty of ways in which it can come to his aid: he can talk about John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay fighting for federal expenditure on internal improvements or about Andrew Jackson’s lack of support for America’s financial infrastructure, namely the Second Bank of the United States, and how this led to the panic of 1837. However, I don’t suggest he re-examine history in the manner which I have just done: “Tea Party Pooper”, for an American, is probably a title best acquired from a distance if at all.