The Dynamics of a Deal

It would be a mistake to assume that any political party is a monolith or anything close to one: people don’t abandon their individual points of view the moment they sign the dotted line of the membership form. I once asked a Tory Member of Parliament, during a period when John Major was struggling with the Eurosceptics, why it was proving so difficult to impose some sort of discipline. He replied, “The only thing which united the Conservative Party was opposition to socialism.” When Labour shifted right and ditched Clause IV, the Conservatives immediately fell to pieces; after the 1997 election, some liberal Tories found it a relatively simple matter to cross the floor. This is by no means a purely Conservative problem: Labour is guilty of letting faction drive the agenda as well. Indeed, the battle between Brownites and Blairites has been more fierce and long lasting than Major’s struggle with the anti-European “bastards”.

It would be a mistake to assume that any political party is a monolith or anything close to one: people don’t abandon their individual points of view the moment they sign the dotted line of the membership form. I once asked a Tory Member of Parliament, during a period when John Major was struggling with the Eurosceptics, why it was proving so difficult to impose some sort of discipline. He replied, “The only thing which united the Conservative Party was opposition to socialism.” When Labour shifted right and ditched Clause IV, the Conservatives immediately fell to pieces; after the 1997 election, some liberal Tories found it a relatively simple matter to cross the floor. This is by no means a purely Conservative problem: Labour is guilty of letting faction drive the agenda as well. Indeed, the battle between Brownites and Blairites has been more fierce and long lasting than Major’s struggle with the anti-European “bastards”.

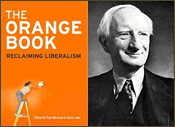

Just because the Liberal Democrats are a smaller party doesn’t mean that they lack similar divisions; indeed, as their organisation is the result of a fusion of two separate political parties, it is entirely natural and predictable that they would have vast areas of disagreement. Broadly speaking, there are two identifiable factions: the “Orange Book” Lib Dems, i.e., those who tend to believe in the free market, and the “Beveridge Group”, who are less trusting of capitalist solutions and more supportive of maintaining public services. The leadership election that took place after Ming Campbell’s departure was essentially a contest between the “Orange Book” and “Beveridge Group” factions, with Nick Clegg representing the former, and Chris Huhne more-or-less standing for the latter. As we’ve seen, the Orange Book tendency won.

If one looks at the list of MPs which comprise the Beveridge Group, it is clear that the election has weakened them: Paul Holmes, the Group’s nominal leader and MP for Chesterfield, lost to Labour. Dr. Evan Harris, one of the most outspoken and eloquent members of the Group, has been sent packing by the Conservatives. Richard Younger-Ross, Sandra Gidley, Paul Rowen, Paul Keetch also lost their seats. David Howarth retired. At the time of writing it is unclear if any of the new intake will replace those who have been dispatched. Meanwhile, prominent Orange Book Liberal Democrats such as David Laws and Vince Cable remain. Under these circumstances, it may be that protests within the Liberal Democrats to a deal with the Conservatives will be relatively muted. Resistance will likely have to arise from the party activists; however, it is difficult to see how such a movement will coalesce in a timely manner, though fortunately they could conceivably rally around Chris Huhne or Simon Hughes.

That said, the Orange Book faction have several potent weapons in their rhetorical arsenal: they can present the party as a moderating influence on what otherwise might be a rapacious Conservative government. They can say they are putting country ahead of politics. If they win on issues such as tax reform, they can also claim a “David versus Goliath” victory. It is entirely possible that some sort of electoral reform, perhaps even a resurrection of the recommendations of the 1998 Jenkins Commission, will be put to a referendum. Such moves may rub balm on the inflamed sensitivities of Liberal Democrat voters and activists. However, tensions will remain: and while the Orange Book group may have enough in common with the Conservatives for a deal to be signed, it’s quite another for it to work on a day to day basis. That said, Labour politicians and others who believe that there is somehow a natural barrier between the Liberal Democrats and Conservatives are kidding themselves. They’re not taking into account the changed disposition of the Liberal Democrat Parliamentary Party, nor looking at the ideological currents which run underneath its public persona. It cannot be said strongly enough: under present circumstances, a deal is entirely possible. What may stay the leadership’s hand is the knowledge that any deal will be unstable, and the thought of the party splitting apart: this was a consequence of previous coalitions between the Liberals and Conservatives. Do the ghosts of Asquith and Lloyd George whisper warnings in Nick Clegg’s ear? Can the party activists raise their voices in time? Or will the Beveridge Group become an anachronism?

I don’t believe that the Orange Bookers are unaware of the risks they are taking; it doesn’t take much for a disagreement to turn into a split, and it may even be that Caroline Lucas isn’t alone for long. After all, the first Green member of the House of Lords, Lord Beaumont, was a defector from the Liberal Democrats. This outcome may seem fanciful at the moment, but this is a time when the range of possibilities is much wider than usual. It all hinges on the the deal and its dynamics, the variety of reactions to the bargain, and the consequences that may ripple outward. There are good reasons why so much caution is being mixed with silence about the negotiations; but it’s perhaps not due to the negotiations being impossible, it’s perhaps because they may be successful.