Switched On

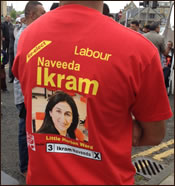

Signs of the imminent election can be seen throughout Bradford: a drive down Upper Rushton Road provides ample evidence of support for Labour’s Councillor Mohammed Shafiq. A few diamond shaped orange Liberal Democrat signs are present along Harrogate Road. Yesterday, I drove through Toller ward and was almost overwhelmed by the number of red banners featuring the visage of Councillor Imran Hussain. In Manningham, a small lorry slowly carried along a massive red, green and white sign advertising the Respect Party, which has apparently been renamed “Respect (George Galloway)” in order to remind people whose party it is. In Little Horton, t-shirts favouring Labour Councillor Naveeda Ikram are all the rage.

Signs of the imminent election can be seen throughout Bradford: a drive down Upper Rushton Road provides ample evidence of support for Labour’s Councillor Mohammed Shafiq. A few diamond shaped orange Liberal Democrat signs are present along Harrogate Road. Yesterday, I drove through Toller ward and was almost overwhelmed by the number of red banners featuring the visage of Councillor Imran Hussain. In Manningham, a small lorry slowly carried along a massive red, green and white sign advertising the Respect Party, which has apparently been renamed “Respect (George Galloway)” in order to remind people whose party it is. In Little Horton, t-shirts favouring Labour Councillor Naveeda Ikram are all the rage.

At home, leaflets from every political grouping imaginable have been shoved through my letterbox, including one from an obscure anti-EU and avowedly xenophobic group of which I had never heard. I performed an experiment with a UKIP leaflet by placing it in one of the cats’ litter trays; they subsequently avoided it, presumably because they thought it was already full.

Feline diffidence aside, this election is crucial for Bradford: at the moment, no party has overall control of the city council. While there are more Labour councillors than any other grouping, this state of affairs makes running the city more tricky than perhaps it should be. Nevertheless, the Westfield Bradford shopping complex is presently being built; the much maligned “Hole” has been filled with a large construction site. On a bright Spring Sunday afternoon, the City Park, also completed by the current council, is a pleasant place where families gather and wade in its vast pool. Should Labour win a majority, there should be more to come; perhaps the council will build upon the emergence of locally-designed products such as the NFC Ring, and bolster the city’s reputation for creating wearable technology.

That said, elections are often unsatisfying spectacles from a technologist’s point of view. A lot of lip service is paid to the digital economy and many politicians are avid users of social media, but a true understanding of modern technology’s potential and pitfalls is not widespread. Furthermore, there have been a lot of false dawns and unfulfilled promises: for example, David Cameron visited Bradford some time ago and pledged super-fast broadband for the city. This has only been partially delivered, and what we do have is due to Virgin Media and the city’s existing cable television infrastructure. The rollout of its rival, BT Infinity, has been botched: many exchanges are fibre enabled, but in order for residents to take advantage of it, work needs to be done at the various junctions. This is by no means uniform: far too few green boxes have the bright sticker saying that it has been set up. The result is a crazy quilt of services, not truly prevalent super-fast availability with proper competition to hold down prices.

Our current national government is not just clueless about broadband on a local level. They also don’t understand that a national plan for faster broadband is necessary to compete in the “global race” which has been so prevalent in Tory rhetoric. South Korea, for example, has started rolling out 1 Gbps broadband throughout their country. Google Fiber is delivering 1 Gbps speeds in Kansas City, and will soon be bringing the same to Austin, Texas and Provo, Utah. Google and South Korea both understand that it’s not possible to have a digital economy without a proper digital infrastructure. In contrast, Britain’s Conservative-led government hasn’t actively courted Google to get them to extend their Fiber service to Britain’s cities; it would be a great boon to otherwise economically struggling towns in the North. Furthermore, considering the taxes that Google should be paying to the Exchequer, it’s the least they could do. Instead, the present government would rather spend £43 billion on new high speed rail services. While high speed rail is often impressive, and is widely perceived as the latest fashion accessory of a modern country, it doesn’t pass the test of a cost-benefit analysis. The current plans for high speed rail are London-centric: they will not extend to places like Wales and Cornwall, which are some of the most deprived regions in Europe. Indeed, by improving the links to London, this may not act as an incentive for businesses to relocate elsewhere, but rather, may cause more economic activity to tip towards the capital.

Admittedly, a national scheme to roll out 1 Gbps broadband would not be cheap; the nearest comparison we have is the National Broadband Network project which was proposed by Australia’s last Labor government. In order to provide high speed broadband to all, it was estimated that the cost would be in the region of £17 billion. Assuming that Australia’s complex geography and vast size incur exceptional costs, it is likely that it would be far cheaper to roll out a similar scheme in Britain; even if inevitable overruns meant that it cost the same or even more than Australia’s plan, it would still be far cheaper than high speed rail, and furthermore, it would be an improvement that reached every corner of the country.

Having said all this, no major political party in Britain has made broadband an issue in the same way that Australia’s Labor Party did in the 2010 election. Nor has any major political party addressed the major economic changes and challenges which are on their way due to new technology.

When the Raspberry Pi single board computer was introduced, it was perceived as a product which would revolutionise technology education. It was thought that a cheap, accessible computer would make it much easier for children to learn how to code. This is true, but the Raspberry Pi, a British invention, has had far greater significance than perhaps was originally intended. This past February, I attended a trade show; I was informed by a gentleman who worked for one of Europe’s most prestigious and stolid passport agencies that they used the Raspberry Pi to develop prototype printing machines. At around the same time, I was told by one of my most forward-thinking technology partners that they believed that future of innovation lay with individual inventors and groups of like-minded inventors (henceforth called hackerspaces) using tools like the Raspberry Pi. This partner also imparted that a lot of companies suffer from an innovation gap: namely, when a scientist in a large firm has a great idea, often this is stopped at the point when the boffin is asked for the potential return on investment. A boffin being a boffin, this is often a puzzling question, as to him or her innovation for its own sake is worth having; furthermore, many boffins simply cannot calculate the return on investment for a particular innovation as it may be unknowable. Indeed, a truly bold innovator will often fly in the face of conventional wisdom. For example, prior to the release of the iPad, Steve Jobs was told that tablet computers were a waste of time. After all, Apple had failed to make money on a previous effort, the Newton. Microsoft had also tried to develop tablet computers and suffered disastrous results. Nevertheless, Jobs believed the innovation proffered by the iPad was worth having as it would revolutionise the market: he was right. But Jobs was a one-off: innovation often remains stunted in corporate silos which are desperately trying not to offend conservatively-minded shareholders.

When the Raspberry Pi single board computer was introduced, it was perceived as a product which would revolutionise technology education. It was thought that a cheap, accessible computer would make it much easier for children to learn how to code. This is true, but the Raspberry Pi, a British invention, has had far greater significance than perhaps was originally intended. This past February, I attended a trade show; I was informed by a gentleman who worked for one of Europe’s most prestigious and stolid passport agencies that they used the Raspberry Pi to develop prototype printing machines. At around the same time, I was told by one of my most forward-thinking technology partners that they believed that future of innovation lay with individual inventors and groups of like-minded inventors (henceforth called hackerspaces) using tools like the Raspberry Pi. This partner also imparted that a lot of companies suffer from an innovation gap: namely, when a scientist in a large firm has a great idea, often this is stopped at the point when the boffin is asked for the potential return on investment. A boffin being a boffin, this is often a puzzling question, as to him or her innovation for its own sake is worth having; furthermore, many boffins simply cannot calculate the return on investment for a particular innovation as it may be unknowable. Indeed, a truly bold innovator will often fly in the face of conventional wisdom. For example, prior to the release of the iPad, Steve Jobs was told that tablet computers were a waste of time. After all, Apple had failed to make money on a previous effort, the Newton. Microsoft had also tried to develop tablet computers and suffered disastrous results. Nevertheless, Jobs believed the innovation proffered by the iPad was worth having as it would revolutionise the market: he was right. But Jobs was a one-off: innovation often remains stunted in corporate silos which are desperately trying not to offend conservatively-minded shareholders.

However, as the Raspberry Pi makes it cheaper for larger concerns (like a passport agency) to innovate, it also makes it easier for individuals and hackerspaces to create inventions which could make their way into mass production. Individuals and hackerspaces can be commissioned to innovate, thus leaping over the current innovation gap. This economic change is empowering: it means that there will be vast networks of craftspeople throughout the world who operate in symbiosis with large firms to deliver the latest and greatest products. This is not a revolution confined solely to the field of electronics engineering, Levi’s is also utilising this model to create new clothes. That said, the current government doesn’t appear to understand or appreciate this enormous change in innovation, development and production. Thanks to the present government, the craftspeople are going to find it much more financially onerous to access higher education at a time when it should be made ever easier to obtain. On a more basic level, the national curriculum as proposed by Michael Gove hasn’t adapted to this changed environment; most children do not receive a Raspberry Pi along with their textbooks. The current government has also not commissioned a new series of standard contracts like the Lambert agreements in order to facilitate contract negotiations between the craftspeople and larger firms. Tax policy is also not geared towards this paradigm shift; it should be. Additionally, the significant breakthroughs in science created by British universities such as graphene are not supported properly. In the case of graphene, China has over 2000 patents utilising this ground-breaking material, the United States, in excess of 1700: Britain only has 50. As these examples illustrate, the government should be there as a partner and facilitator; however, the prevalent ideology of the current regime states that all one needs to do is abscond from the marketplace and all will be well. This ideology is buttressed by hypocrisy: the Tory-led government has actively intervened in the housing market, creating the sugar-rush sensation of prosperity caused by a house-price bubble.

The 2014 campaign has not been animated by such long-term issues: the appalling, yet colourful bigotry of UKIP candidates throughout the land has obscured the intellectual poverty of the current Conservative-led government. Their sole idea is to continue to privatise instead of build. This propensity has been taken to absurd lengths; Michael Gove’s Department of Education has proposed privatising child protection services, which would instantly change their mission statement from the simple, wholesome purpose of helping children to making money for shareholders. The Tories’ Liberal Democrat partners would like us to focus on the tax breaks they secured for the lower paid, though their backing of higher tuition fees has laid a bear trap for the innovation economy we need. This is not to say Labour is perfect: it has its share of technophobes. But at least Labour has one idea that marks it out, which shows that it is the party most capable of being “Switched On”: it believes the state should take an active role. It means that with Labour, education stands a chance of becoming more accessible and relevant, it means there is the possibility that HS2 could be cancelled and National Broadband implemented, it suggests that the necessary foundations for the future economy could be set down. The election of 2014 is a crucial milestone in this journey. So, on Thursday, I’ll get up early, feed the cats, drink my coffee, and get dressed; hopefully it will be a bright morning as I take a brief walk to my polling station. When I get there, I’ll present my polling card and take up a pencil to mark my ballot; it won’t take me long to tick the boxes beside the names of the Labour candidates.