Forever Bradford

In a few days time, and after three and a half eventful years, I will no longer be living in Bradford. As I type this, the sun is shining and the skies are blue on a lovely May afternoon that is beginning to fade into evening. Given such a scene, it’s difficult to contemplate leaving: but I know that very soon I will embark on a new life in rural Cambridgeshire.

In a few days time, and after three and a half eventful years, I will no longer be living in Bradford. As I type this, the sun is shining and the skies are blue on a lovely May afternoon that is beginning to fade into evening. Given such a scene, it’s difficult to contemplate leaving: but I know that very soon I will embark on a new life in rural Cambridgeshire.

The reason for my move is economic. It is much more difficult to find a job in this region than it is in southern, sunnier climes. Cambridgeshire, or at least the part of it I will inhabit, has the benefit of being in London’s orbit without being too influenced by its proximity. My new home has an extensive vegetable garden and views over flat farmland. It will also be my first time living in the East of the country; I have lived in London, Yorkshire and various parts of the South.

A new experience and a new life: there is much to anticipate and enjoy. Already, I am looking forward to waking up in the morning and viewing the flat, open horizons out my bedroom window. Yet, I do have regrets about what I am about to leave behind.

My last days in Bradford may have been lived more intensely than previous, particularly during the run up to the General Election. While I wasn’t really involved in the General Election, I did some leaflet stuffing for Labour’s local election candidate. It was a miserable business on the evenings in which I participated: the winds were high and cold, it was as if they were pushing me and my fellow canvassers down the narrow streets lined with terraced houses made of alabaster brick. The evening sky had a blue sheen as if it had been frozen into place.

There was a particular art to stuffing leaflets: fold the leaflet in half, try and push through the slot quickly, avoid the barking dogs whenever possible. The weather and the drudgery of the task made partisanship fade: I passed by a Liberal Democrat activist who was embarked on a similar task and we greeted each other politely.

Election Day itself was thankfully sunny and warm in Bradford. My fiancée and I voted as early as possible and then went to Labour’s local campaign headquarters, which was set up in a local sports club. Red clipboards with sheets full of addresses were provided to teams of four, and then the teams dispersed to various neighbourhoods, knocking on doors, trying to ensure that those who had promised to vote Labour had the opportunity to get out and do so.

It was also a reminder of why the election was so important: some of the neighbourhoods through which I trod are among the most deprived in Britain. Unemployed or irregularly employed people were at home to answer the door. Some homes had iron gates on the doors and windows, with a notice indicating they had been repossessed. Some who answered our calls were migrants who barely spoke a word of English. One elderly gentleman whose home was surrounded by a colony of cats looked emaciated, nearly desiccated by time; an odour of stale cigarette smoke and mould hung over his residence.

Perhaps the most poignant reminder of how far from the luminous picture painted by Tory rhetoric that Bradford remains came from some very basic apartments made of grey brick. They were placed in a set of box-like buildings positioned at the end of a road that ran through a deprived neighbourhood. The apartments were immune to personalisation from the outside, except for one intrepid individual who put out a blue folding chair and some flower pots. I was informed that the inhabitants were mainly elderly, living on minimal incomes. The wind rose up again. It seemed a terribly lonely place, the only sound being with only the idle chatter of birds in some nearby trees.

As homes were visited the sheets were marked: Voting Labour, Not Voting, Voting Other, Not In. Then they were driven back to the campaign headquarters where yet another red clipboard awaited. Eventually, the sun set: there was a genuine chill in the air. Voters became annoyed with being pestered. It was time to dump the remaining red clipboards in and wait for the results.

I was fortunate to have a role in the local election, namely, I was a poll watcher: that meant I was given entry to the ballot verification process which happened on Election Night, and then to the count for the local elections the following day. A friend stayed with my fiancée and I: we caught the exit poll on BBC just before departing for verification. We were floored: every last poll we had seen had indicated that a hung parliament was in the offing. We all thought that Ed Miliband was going to have to make a deal with the SNP as well as the Liberal Democrats: like many of us, I thought just do it, get it done, give Scotland a few billion, get Cameron out of Downing Street, it’s for the best.

Right up until the exit poll, this scenario not only seemed possible, but likely. But then the clock struck ten and its chimes shattered the fantasies of what tomorrow would bring: it was immediately clear that the Tories were going to form the next government.

As I drove to the large sports hall where the count took place, I pondered what had happened. It was dark: only the illumination of the orange street lights and the occasional sign of a petrol station lit our way. Could the exit poll have been wrong, I wondered. Once a few results came in, it didn’t seem so. Had people been shy? Had they lied to the pollsters? Had our ground operations been ineffective? What happened?

I had a ticket which gave me access into the polling place: a plastic band was put around my wrist. A set of stairs and I was in the place where the counting takes place.

Americans and others may find the British system of counting votes to be archaic, but there is a certain charm associated with it. There are two distinct tribes: the first is the counters and their supervisors, the other, the politicians and activists. The politicians and activists all wore rosettes or buttons to identify their allegiance. The large number of people wearing purple UKIP rosettes disquieted me. Labour folk like me were in abundance as were grim looking Liberal Democrats. The Tories and Greens were also in force. Strangely, however, the red and green rosettes of Respect were few and far between: this seemed odd at the time given that George Galloway’s defeat was by no means certain or even predicted. Two bodyguards accompanied one Respect supporter who sported a grey beard, a hat very similar to Galloway’s and a long black overcoat. He floated around the hall like a listless shadow with his minions and then departed into the night.

On Election Night, the task insofar as the local election was concerned was not to count the vote, but to verify the ballots. The idea is to match up the number of ballots to the number of votes cast.

The counters are an interesting lot: they appear to be from every walk of life and of every age. One elderly lady who wore black plastic frame glasses on the end of her nose and a purple cardigan fascinated me. She had a green rubber thimble which she kept positioned on her thumb as she swiftly sorted through the votes. My task was to stand in front of the counters and watch them as they worked. I also was there to get a rough idea of how well my candidate was doing. By my count, it was close: the area in which I lived was predominately Liberal Democrat, though UKIP appeared to be making significant inroads. A Labour candidate would find it tough going; nevertheless, it was tight.

It took time for all the black metal boxes full of the beige coloured ballots to arrive: the verification proceeded fitfully. More news filtered in: the Tory vote had held up, they seemed to have cannibalised their coalition partners. As a result, the Liberal Democrats would be lucky to retain 8 parliamentary seats. This spelled doom for the Liberal Democrat MP for my part of Bradford, though he had the slight consolation that his vote held up better than most: a decline of a little over 4 percent compared to a national drop of over 15 percent.

There were few places to sit in the hall. When exhaustion finally set in, I sat against the wall with a can of diet cola. Twitter was still bubbling and erupting: it looked as if we were headed for a Tory majority government. My feet were sore, the red rosette pinned to my jacket seemed rather like a symbol of noble defiance that in the end proved ineffective. The smiles on the faces of those who wore blue rosettes were impossible not to notice.

The verification finally finished after 2 AM. My fiancée and I went home: the streets were empty. Everyone sensible was asleep. The news came over the radio that in Belfast East, brave Naomi Long who had defeated the antediluvian Peter Robinson back in 2010 had herself been beaten by one of Robinson’s people. The night’s darkness hung like a pall over our route home.

I didn’t go to bed. Our friend was still up in our living room collating the results and I positioned myself on a sofa, slipping in and out of consciousness while watching the results. I woke up when Galloway was banished: this was a thrill for me, given how the Respect Party had been tweeting pictures of Galloway and his motorcade proceeding through the Manningham section of Bradford. Hubris had been followed by Nemesis with haste. I saw Labour seats in Scotland fall like bowling pins, knocked over by the yellow and black SNP wrecking ball. Douglas Alexander lost to a university student. Gordon Brown’s old constituency changed hands. Jim Murphy was booted.

Dawn came. My feet still hurt. I went upstairs and made coffee and tried to absorb the results. Bradford East, West and South had all gone Labour; but nationally, the Tories were headed for a majority of 12 with 331 seats, unless by some miracle the Liberal Democrats had somehow held onto some redoubts in the South West. But Danny Alexander was gone, Vince Cable was gone, it seemed unlikely that Andrew George would be spared.

We went to our count; again, I stood over the counters. In this case, we were watching various votes being sorted into particular piles for counting purposes. I watched the Liberal Democrat votes like a hawk, looking for any ambiguous or incorrect ballots being put into the bundles. The counters check each other’s work and sign off each pile. In the end there was only one item that was out of order: one Tory vote had accidentally made it into the Liberal Democrat stacks.

In the end, this count was one of the few Liberal Democrat triumphs of the evening: my candidate was beaten by 134 votes. UKIP’s inroad into certain working class areas was probably to blame; or rather, it was our failure to appeal to the same people. As the returning officer took the podium and read out the result, I cheered my candidate, and felt pain in my stomach as the Liberal Democrat’s superior tally was revealed. I took off my red rosette and stuck it in my jacket pocket: there it has remained.

It had started raining earlier in the day, but by the time the count finished it was coming down in earnest. Radio 4 was full of prognostications about what the new, unfettered Conservative government would do. I thought of the people we met while canvassing: their lives would not improve. Rather, through schemes like the so-called “Northern Powerhouse” no doubt the Government will “outsource” the responsibility for these people to others and then outsource the blame for failure. As we drove, we passed by the office for our former Liberal Democrat MP. His staff were hastily clearing out their equipment and taking down signs: one well known local councillor was taking out plastic bags amidst the deluge.

Later, my fiancée and I had dinner in Leeds at a sushi restaurant. I kept checking my phone and tried to understand what had happened. I still am coming to grips with it, but I believe what occurred is that people saw the possibility of change, but they were sufficiently frightened by Tory propaganda to believe it would be dangerous. When you have little, you are naturally afraid that you will lose what tiny patch of this earth that you’ve acquired. Labour did best in places like London, i.e. cities that embrace change as a matter of course; Labour also did well in Bradford, a place where many had nothing to lose.

It was still raining when we finally returned home. I surrendered to fatigue and we went to bed early; as I pulled the duvet over me and listened to the rain falling, I realised it had been a depressing day, but a uniquely interesting 48 hours. I had pounded the pavements of Bradford, I’d taken an active if small role in its politics, I was witness to the process of democracy and saw its pitfalls up close. It was symbolic of my time in Bradford: I had a chance to live life intensely, passionately and full of purpose. I also got a chance to see the world just by living in one place, given all the cultures that inhabit its melting pot. I lived amidst the hills of Bronte Country as well as in the dining room of Café Zoya. I died a little when Galloway was elected in 2012 and my heart soared when Bradford City beat Chelsea. It hasn’t always been easy to live here, but it has been wonderful. If I find a life in Cambridgeshire, where the sky hangs low over the flat land, that is half as interesting as what I led in Bradford, I will consider myself lucky. I will never forget, and part of me will be forever left in Bradford.

I owe Tony Benn a great deal. While he was Minister for Technology between 1966 and 1970, Mr. Benn created a British equivalent to IBM, International Computers Limited. Although its history was not trouble free, it was a success story; it was there that I began my working life after I graduated from University. It was there also that I was first introduced to the internet. In short, it was my experiences at ICL that enabled me to build my career and the interesting life that followed. Without Tony Benn, it’s entirely possible that I could have begun my journey at another point, but that’s not what happened. Tony Benn was a champion of modern technology, and thanks to him being the person that he was, I am the person that I am today. He encouraged me.

I owe Tony Benn a great deal. While he was Minister for Technology between 1966 and 1970, Mr. Benn created a British equivalent to IBM, International Computers Limited. Although its history was not trouble free, it was a success story; it was there that I began my working life after I graduated from University. It was there also that I was first introduced to the internet. In short, it was my experiences at ICL that enabled me to build my career and the interesting life that followed. Without Tony Benn, it’s entirely possible that I could have begun my journey at another point, but that’s not what happened. Tony Benn was a champion of modern technology, and thanks to him being the person that he was, I am the person that I am today. He encouraged me. The film presents some fascinating “what ifs”. One of the most intriguing is what may have happened if Benn had continued as Minister for Energy. He was responsible for the creation of Britain’s oil industry, and thanks to his efforts the UK reaped the benefit of what lay beneath the North Sea. However, Labour lost the 1979 general election and it was Margaret Thatcher who cashed in. Rather than save the money (as Benn intended) or invest it in modernising British industry (as Benn also wanted), she used oil revenues to fund unemployment benefit (after she caused British manufacturing to collapse) and tax breaks for the well off. We suffer from this legacy today; one of the questions which animates the Scottish independence movement is what precisely happened to the endowment that Benn arranged for them.

The film presents some fascinating “what ifs”. One of the most intriguing is what may have happened if Benn had continued as Minister for Energy. He was responsible for the creation of Britain’s oil industry, and thanks to his efforts the UK reaped the benefit of what lay beneath the North Sea. However, Labour lost the 1979 general election and it was Margaret Thatcher who cashed in. Rather than save the money (as Benn intended) or invest it in modernising British industry (as Benn also wanted), she used oil revenues to fund unemployment benefit (after she caused British manufacturing to collapse) and tax breaks for the well off. We suffer from this legacy today; one of the questions which animates the Scottish independence movement is what precisely happened to the endowment that Benn arranged for them. Some films are meant to be taken at face value: a car chase is a car chase, an explosion is an explosion, and they are there solely to get the adrenalin pumping and to attract the eye. Other films are purposefully deeper: for example, the German film, “The Lives of Others” is designed to stimulate both thought and emotion. It’s a rare film that can be taken both at face value yet offers a great deal to consider. “Gone Girl”, starring Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike, based upon the best selling novel by Gillian Flynn, is of this extraordinary type.

Some films are meant to be taken at face value: a car chase is a car chase, an explosion is an explosion, and they are there solely to get the adrenalin pumping and to attract the eye. Other films are purposefully deeper: for example, the German film, “The Lives of Others” is designed to stimulate both thought and emotion. It’s a rare film that can be taken both at face value yet offers a great deal to consider. “Gone Girl”, starring Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike, based upon the best selling novel by Gillian Flynn, is of this extraordinary type. Thankfully, the film scratches this altogether too pristine surface and shows the pathology which lies underneath. For example, we are introduced to Amy’s parents (played by Lisa Banes and David Clennon), who are brazenly neurotic: they have authored a series of children’s books about Amy’s life, entitled “Amazing Amy”, and every volume they’ve produced is an improvement on the daughter they actually have. The fictional Amy is a virtuoso at the cello, while the “real” Amy gave up the instrument long ago. The fictional Amy played varsity volleyball, while her “real” counterpart did not excel.

Thankfully, the film scratches this altogether too pristine surface and shows the pathology which lies underneath. For example, we are introduced to Amy’s parents (played by Lisa Banes and David Clennon), who are brazenly neurotic: they have authored a series of children’s books about Amy’s life, entitled “Amazing Amy”, and every volume they’ve produced is an improvement on the daughter they actually have. The fictional Amy is a virtuoso at the cello, while the “real” Amy gave up the instrument long ago. The fictional Amy played varsity volleyball, while her “real” counterpart did not excel. Recently, I was introduced to the television series “Breaking Bad”. I’m not 100% sure why this had passed me when it was originally on the air; perhaps the hype surrounding it had the effect of blunting its appeal.

Recently, I was introduced to the television series “Breaking Bad”. I’m not 100% sure why this had passed me when it was originally on the air; perhaps the hype surrounding it had the effect of blunting its appeal.

These people were young once. They had homes, jobs, families, arguments, dates on Friday nights and sleepy Saturdays that followed. They combed their hair that was once a colour besides grey, they watched television, they drove too fast, they drank too much, they washed their cars and did the shopping. Time seemed to be on their side, but time is also cruel: body parts wear out, the eyes dim, the lungs don’t suck in air as readily as they once did, and blood vessels harden. If one is unlucky, then parts of the brain will be attacked by a shadow enemy, leaving a patch of the mind shrouded in darkness either from a rush of blood or a lack of it. That which makes us human: our thoughts, our dreams, our perceptions are all under assault from a stroke. The wreckage washes up onto the Stroke Ward, where nurses, doctors, support staff and therapists are all lost in lightly masked perplexity as they try to reassemble the pieces.

These people were young once. They had homes, jobs, families, arguments, dates on Friday nights and sleepy Saturdays that followed. They combed their hair that was once a colour besides grey, they watched television, they drove too fast, they drank too much, they washed their cars and did the shopping. Time seemed to be on their side, but time is also cruel: body parts wear out, the eyes dim, the lungs don’t suck in air as readily as they once did, and blood vessels harden. If one is unlucky, then parts of the brain will be attacked by a shadow enemy, leaving a patch of the mind shrouded in darkness either from a rush of blood or a lack of it. That which makes us human: our thoughts, our dreams, our perceptions are all under assault from a stroke. The wreckage washes up onto the Stroke Ward, where nurses, doctors, support staff and therapists are all lost in lightly masked perplexity as they try to reassemble the pieces. I can imagine what the remainder of the United Kingdom would be like without Scotland. Once the divorce became final, no doubt the country would be sombre, an emotional state brought about by the departure of a certainty. I suspect that an updated Union Flag would reflect the prevailing melancholy: the simplest change would be to replace the royal blue of the Saltire with the black of Wales’ St. David’s flag. This revised banner, however, would look like the drapery for a funeral when it is deployed on occasions of national importance. Good taste would dictate that “Rule Britannia” could be never sung again at the Last Night of the Proms: perhaps it will be replaced by a tearful rendition of “Jerusalem”. No doubt there would be some clamour among expatriate Scots for access to channels from the new Scottish Broadcasting Service so they could sing along to “Flower of Scotland” at their own Prom. When the UK Prime Minister goes to Brussels or Geneva for summits, he or she may be a diminished figure: I can imagine the shifty glances exchanged once their Scottish counterpart arrives on the scene. It may very well be that in a fit of pique, the remainder of the UK will decide to leave the European Union. The bustle and colour brought in by European immigrants to cities like London and Manchester will soften and fade. It would be a quieter country, to be sure.

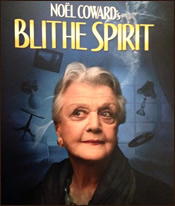

I can imagine what the remainder of the United Kingdom would be like without Scotland. Once the divorce became final, no doubt the country would be sombre, an emotional state brought about by the departure of a certainty. I suspect that an updated Union Flag would reflect the prevailing melancholy: the simplest change would be to replace the royal blue of the Saltire with the black of Wales’ St. David’s flag. This revised banner, however, would look like the drapery for a funeral when it is deployed on occasions of national importance. Good taste would dictate that “Rule Britannia” could be never sung again at the Last Night of the Proms: perhaps it will be replaced by a tearful rendition of “Jerusalem”. No doubt there would be some clamour among expatriate Scots for access to channels from the new Scottish Broadcasting Service so they could sing along to “Flower of Scotland” at their own Prom. When the UK Prime Minister goes to Brussels or Geneva for summits, he or she may be a diminished figure: I can imagine the shifty glances exchanged once their Scottish counterpart arrives on the scene. It may very well be that in a fit of pique, the remainder of the UK will decide to leave the European Union. The bustle and colour brought in by European immigrants to cities like London and Manchester will soften and fade. It would be a quieter country, to be sure. It’s difficult for me to say when I first became aware of Angela Lansbury. Perhaps it was due the Disney film “Bedknobs and Broomsticks” in which she played the trainee witch Eglantine Price. It may have been when I saw her on television in the long running series “Murder She Wrote”. She certainly caught my attention as Raymond Shaw’s domineering mother in the 1962 film, “The Manchurian Candidate”: her speech about making “Martial Law seem like anarchy” chilled me to the bone. On the other hand, I was captivated by her luminescent beauty when she portrayed Princess Gwendolyn in Danny Kaye’s 1956 comedy, “The Court Jester”. All told, she has been a constant on my television screen and in the cinema; any film or programme that featured her was indicative of quality.

It’s difficult for me to say when I first became aware of Angela Lansbury. Perhaps it was due the Disney film “Bedknobs and Broomsticks” in which she played the trainee witch Eglantine Price. It may have been when I saw her on television in the long running series “Murder She Wrote”. She certainly caught my attention as Raymond Shaw’s domineering mother in the 1962 film, “The Manchurian Candidate”: her speech about making “Martial Law seem like anarchy” chilled me to the bone. On the other hand, I was captivated by her luminescent beauty when she portrayed Princess Gwendolyn in Danny Kaye’s 1956 comedy, “The Court Jester”. All told, she has been a constant on my television screen and in the cinema; any film or programme that featured her was indicative of quality. It’s at this moment that the character of Charles comes into his own: he presents the dilemma of a man who essentially has two wives, one living and one passed on, possessing contrasting virtues, both present at the same time and both wanting him to themselves. He intimates that he feels terribly guilty about the death of one wife, and yet he says he doesn’t want to be unkind to the one who is alive. That said, the play is sufficiently honest to show a moment in which Charles makes it clear that he would like both wives to be around, engaging him in a sort of cosmic ménage a trois. Charles is also insufferably vain throughout: it’s unclear if his concern for either wife stems from actual love, his desire to maintain his self-image or just to stop being nagged. The play suggests it’s a combination of all of the above, with love being the lesser ingredient in the mix.

It’s at this moment that the character of Charles comes into his own: he presents the dilemma of a man who essentially has two wives, one living and one passed on, possessing contrasting virtues, both present at the same time and both wanting him to themselves. He intimates that he feels terribly guilty about the death of one wife, and yet he says he doesn’t want to be unkind to the one who is alive. That said, the play is sufficiently honest to show a moment in which Charles makes it clear that he would like both wives to be around, engaging him in a sort of cosmic ménage a trois. Charles is also insufferably vain throughout: it’s unclear if his concern for either wife stems from actual love, his desire to maintain his self-image or just to stop being nagged. The play suggests it’s a combination of all of the above, with love being the lesser ingredient in the mix. I often find myself in London the day after a major British election. I was here when it was confirmed that Boris Johnson had been re-elected as Mayor; it was as if some hidden force was compelling me to press my nose up against that spectacle. At just about the time that the result was announced, I walked past a storm grate from which a powerful stench arose: it seemed as if the city itself was suffering from terrible flatulence. When Tony Blair triumphed in 1997, I was staying at my parents’ London home: it was a summer’s day brought forward to May, and the sun was so radiant that the blue sky had turned almost white. I remained glued to my television set throughout the day as Blair proceeded to Buckingham Palace and then on to cheering crowds at Downing Street. Now that the 2014 local election has concluded, perhaps strangely, I am here again.

I often find myself in London the day after a major British election. I was here when it was confirmed that Boris Johnson had been re-elected as Mayor; it was as if some hidden force was compelling me to press my nose up against that spectacle. At just about the time that the result was announced, I walked past a storm grate from which a powerful stench arose: it seemed as if the city itself was suffering from terrible flatulence. When Tony Blair triumphed in 1997, I was staying at my parents’ London home: it was a summer’s day brought forward to May, and the sun was so radiant that the blue sky had turned almost white. I remained glued to my television set throughout the day as Blair proceeded to Buckingham Palace and then on to cheering crowds at Downing Street. Now that the 2014 local election has concluded, perhaps strangely, I am here again. Perhaps, however, he doesn’t qualify for the moniker of the “saddest” member of UKIP; that may be Neil Hamilton. For those unfamiliar with Mr. Hamilton, he along with his wife Christine, is more a reality television personality than an actual politician. The couple were infamous for providing documentary maker Louis Theroux with one of the weirdest of his “Weird Weekends” in which Christine made her unseemly attraction to Mr. Theroux quite plain. More seriously, the Hamiltons were implicated in a Cash for Questions scandal prior to the 1997 election. At that point, anti-corruption campaigner Martin Bell arrived wearing his white suit, and rather like a latter day Gandalf, drew the poison of the corrupt couple out of their Tatton constituency. Nevertheless, the Hamiltons were unable to take the hint that a period of prolonged if not eternal silence would be apropos. They left the Tories, joined UKIP and subsequently thrust themselves back into the limelight. Hamilton just tried to win a council seat in Wandsworth; he only accrued 396 votes, which presumably were from people who had never heard of him. He appeared on Channel Four News after this resounding defeat and spoke of the environment in London being challenging as so many of its denizens had been born elsewhere. The word “cosmopolitan” was also thrown into the mix. This impolitic outburst followed similarly simultaneously flattering yet denigrating comments by Suzanne Evans, a UKIP spokesperson, who said that her party had problems gaining support from the “educated, cultural and young.”

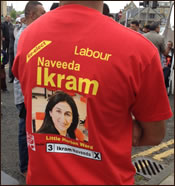

Perhaps, however, he doesn’t qualify for the moniker of the “saddest” member of UKIP; that may be Neil Hamilton. For those unfamiliar with Mr. Hamilton, he along with his wife Christine, is more a reality television personality than an actual politician. The couple were infamous for providing documentary maker Louis Theroux with one of the weirdest of his “Weird Weekends” in which Christine made her unseemly attraction to Mr. Theroux quite plain. More seriously, the Hamiltons were implicated in a Cash for Questions scandal prior to the 1997 election. At that point, anti-corruption campaigner Martin Bell arrived wearing his white suit, and rather like a latter day Gandalf, drew the poison of the corrupt couple out of their Tatton constituency. Nevertheless, the Hamiltons were unable to take the hint that a period of prolonged if not eternal silence would be apropos. They left the Tories, joined UKIP and subsequently thrust themselves back into the limelight. Hamilton just tried to win a council seat in Wandsworth; he only accrued 396 votes, which presumably were from people who had never heard of him. He appeared on Channel Four News after this resounding defeat and spoke of the environment in London being challenging as so many of its denizens had been born elsewhere. The word “cosmopolitan” was also thrown into the mix. This impolitic outburst followed similarly simultaneously flattering yet denigrating comments by Suzanne Evans, a UKIP spokesperson, who said that her party had problems gaining support from the “educated, cultural and young.” Signs of the imminent election can be seen throughout Bradford: a drive down Upper Rushton Road provides ample evidence of support for Labour’s

Signs of the imminent election can be seen throughout Bradford: a drive down Upper Rushton Road provides ample evidence of support for Labour’s  When the

When the  It was serious. Normally, a litter tray at the end of the day is a mess, but this time, it was a horror show. My fiancée had called me down to take a look: up until that point, it had been a normal work day, with its usual hastily consumed cups of coffee, teleconferences and writing documents and emails. I had driven home and changed into more comfortable clothes; I anticipated nothing more than a little dinner, a little television, another check on work e-mails, and then a chance to sleep.

It was serious. Normally, a litter tray at the end of the day is a mess, but this time, it was a horror show. My fiancée had called me down to take a look: up until that point, it had been a normal work day, with its usual hastily consumed cups of coffee, teleconferences and writing documents and emails. I had driven home and changed into more comfortable clothes; I anticipated nothing more than a little dinner, a little television, another check on work e-mails, and then a chance to sleep. As I looked at Thomas laying on the ottoman, his face serene yet somehow suffering, I wondered if all that would be gone. I knew that if consulted others, many would say, “He’s just a cat”. Perhaps he had more personality and eccentricities than most: after all, he has a passion for eating cake. But to many, he would still remain “just a cat”.

As I looked at Thomas laying on the ottoman, his face serene yet somehow suffering, I wondered if all that would be gone. I knew that if consulted others, many would say, “He’s just a cat”. Perhaps he had more personality and eccentricities than most: after all, he has a passion for eating cake. But to many, he would still remain “just a cat”. I'm a Doctor of both Creative Writing and Manufacturing and Mechanical Engineering, a novelist, a technologist, and still an amateur in much else.

I'm a Doctor of both Creative Writing and Manufacturing and Mechanical Engineering, a novelist, a technologist, and still an amateur in much else.